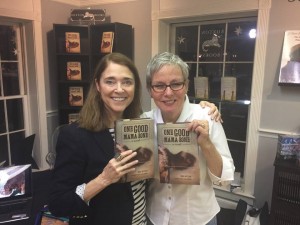

Bren McClain is a writer who never gave up, a former journalist turned award-winning fiction writer. Her first novel, One Good Mama Bone, was recently published by Story River Books, Pat Conroy’s original southern fiction imprint with USC Press. McClain sat down with me to talk about farm life, writing, and a secret that would stay with her for many years before becoming the seed for her first novel.

This interview has been edited for length.

Mindy Lucas: Welcome to Porch Talk, Bren. You’ve been on tour for One Good Mama Bone. How’s that going? Have there been any surprises or anything you didn’t expect from readers who have turned out for that?

Bren McClain: Well I named the book tour the “Mama Bone Barnstorm Tour.”

ML: I love that.

BM: I’ve now done two events in my hometown of Anderson, South Carolina, but I came back home after Monday night’s event and I just cried at the love and support that is being shown. The outpouring of love, the questions about Mama Red, loving my character Sarah in the book, and just a real, real response from readers. I was in bed that night and thought, man, I should have called it the “Mama Bone Love Tour.” But Mindy, it’s been fantastic. I’ve done 10 stops so far and we have sold out of books at four of the 10 stops.

ML: That’s great!

BM: Yes, the response has been wonderful.

ML: So you grew up in Anderson and studied English at Furman. You were raised on a beef cattle and grain farm. How much of that affected not just your love of nature but formed who you are today and your decision or desire to write and become a writer?

BM: Let’s go with the top number – 100 percent. T-totally through and through it formed and shaped me. The land, the animals, the expansiveness of the sky, liking to be by myself. I used to pack a canteen of water and a peanut butter sandwich. My mom used to say when I was a little, itty bitty girl, I would go to the back of the pasture at the highest point and just sit with a notepad and pencil.

Everything I am today, if you unpacked me right now today, you would find the components of my childhood. You would find the farm. You would find nature and the land. You would find the animals. Liking to be outside, the solitariness it takes to write a novel – all of those things, my love of writing. You wouldn’t find anything else in this body but the 3-year-old Bren McClain.

ML: You know, I wasn’t trying to tie in to Pat here, but it’s interesting that you described your childhood in that way, because I immediately thought of his description of growing up in the Lowcountry from The Prince of Tides where he says I would have to take you to the marsh on a spring day…open you an oyster with a pocketknife and feed it to you from the shell and say…. “That’s the taste of my childhood.” And then of course he described the smell of pluff mud. Do you think where you’re from and how you grew up stays with you or ultimately forms who you’ll become?

BM: Yes, I’m not sure I’m anything but that. I spent my 20s and 30s, when you spread your wings, in different places, Asheville, etc. I was in television news.… So I had that big city life. But then I bought an acre at Edisto Island, built a barn. So I got out of that city life and went right back. I made my house into a barn. I had no sheet rock in it. It was all recovered barn wood. I stayed there until I needed more land and so I now live on 100 acres outside of Nashville.

ML: And so One Good Mama Bone—which is a great title by the way—was just recently published in February 2017. But prior to this you won a number of awards. You were a two-time winner of the South Carolina Fiction Project, recipient of the 2005 Fiction Fellowship by the South Carolina Arts Commission, you won the 2016 William Faulkner–William Wisdom Novel-in-Progress for “Took” and you were a finalist in the 2012 Pirate’s Alley Faulkner Award for Novel-in-Progress for One Good Mama Bone.

And so I read where you called yourself a “27-year-overnight success” but you must have had some sense that you were on to something with this writing thing. So I guess my question isn’t about persistence so much as it is about philosophy. Do you believe a story has a life and a timing of its own and takes however long it takes?

BM: Oh yeah. I would never ever have thought, in my youth, that it would have taken this long. But I’ll tell you, Mindy, looking back on it, it’s absolutely perfect. To have been ushered in and escorted by Pat Conroy’s enormous heart. That’s the pinnacle, literary world to me. So I’m glad that it never happened before now.

I believe that writers have stories that are ours and ours alone to tell. And so I anchor in that. I believe heartily in that. I believe that if I have a story to tell, it’s going to find its way.

I wrote one noveI…but it was totally made up, made from, as Reynolds price used to say, “from whole cloth.” But that was what the first novel was—made up. But in June of 1993, I was living in Atlanta in midtown. I rented a room in an apartment in a house and this neighbor of mine said he wanted to talk to me. This was unusual because we had never really had a conversation before.

I knew his name was Ron and he had a white, convertible Cadillac and he had a great suntan. So I go sit on his front porch and he tells me, ‘I turned 60 today.’ So I went, ‘Oh Ron, well Happy Birthday.’ And he said, ‘I only tell you that because I’ve been carrying around this secret since I was 6 years old. Fifty-four years I’ve been carrying this secret. My mom made me promise that I’d never tell. And I’ve been true to that, but I can’t be true to that anymore.’

Then he looks over at me. I’m sitting in a white wicker chair with my hands on the arms. And he says, ‘I’m choosing you to tell knowing you’re a writer.’ And I remember squeezing that wicker and the sound that it made.

So he proceeds to tell me about this night outside of Birmingham, when he was 6 and he was summoned to the kitchen from his bed and made to stand in the doorway and watch the birth of this baby. It was their neighbor having the baby lying on the kitchen table.

So, unlike what happens in my book, it was something horrible that happened and his mother made him go get a shovel and be apart of it. And this broken man sitting in front of me in that chair is telling me this with tears and I’m knowing in my soul, oh my, this is being giving to me to write about. This is my story to write about. I got up off that porch, thought I would go make some notes so I wouldn’t forget, but could not dare write one word down.

Six years later I’m in Assisi, Italy, studying with Dorothy Allison and she makes an assignment. Something about mothers. So remember I’m sitting in this twelfth-century villa with the window open looking out on this gorgeous countryside. And the words came to me, ‘One night my momma got me up out of bed.’ And I began writing in the voice of a 6-year-old boy. From that, over a couple of years, I wrote that novel and while I wrote it, I fell in love with the mother, because I figured out how she was wired and why she did what she did.

However, not one soul who read it said anything but this. ‘Oh Bren. No, no. Nobody will read this. This is horrible. The woman is a monster.’ And I would say, ‘But I love her.’ And they would say, ‘Well, it’s not on the page.’

It took me awhile to admit that it was a failed novel. I had no idea how to fix it and started on the research for another book—the novel I’m writing now. But one day in 2008, I was visiting this same farm, where I am right now (in Anderson), and it was in the midst of weaning where the babies are taken away from their mommas at age 6 to 8 months. It’s a standard farming practice.

So about 4:00 or 5:00 in the morning, there were these guttural sounds of mooing from the mamas and the babies calling back and forth to each other. It made me put a jacket and boots on and go out to the pasture and there huddled in the corner were these mother cows and they were making just these guttural, guttural calls for their babies. And their eyes would cut to me and seemed to ask, seemed to plea, “Can’t you bring my babies back?”

And then I had these chills just come up my body because I thought of that novel, that failed novel. The intent had always been to honor motherhood. So I knew then that I had found the missing piece. So I made a promise to the mama cows that I would tell their story and then came back and threw out 95 percent of the book and just kept that little piece that Ron had told me. And I kept looking at it and I said, you know this may have been the way it happened, but I started to remember what a North Carolina writer, Randall Kenan said. He said, ‘In order to write fiction, you have to get the journalism out of the way.’

So what I had done is I had written that failed novel and had really kept the journalism…so I gave myself license to morph it and so that’s what I did.

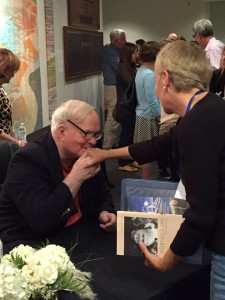

ML: In the foreword by Mary Alice Monroe, she talks about what you might call a serendipitous meeting with Conroy in the line of one his famously long, marathon book signings. Can you talk a little about what that meeting was like and what it ultimately came to mean to you?

BM: So I’m in Charleston the summer of ’95, the year I moved to Edisto in one of those long, long lines. And I get up to him and I’m shaking all over and I tell him, “I’m a writer too” in this little mouse voice. And he just stopped his pen and looked up at me and said, “Oh really? Wonderful. What are you writing?”

This was that first novel. And do you know, he wrote his agent’s name and address and phone number and gave that to me. He said, “You finish that book and you contact him.” And then he wrote, “I hope to read your work one day” in my inscription. And of course I thought, “Oh right.” And you know, I didn’t even follow up on it. It was so fantastic in my mind to think that Pat Conroy would give me his agent’s contact info.

See that part I’m talking about? That magnanimous, can’t-do-enough-for-you, can’t-make-you-feel-special-enough. Takes it all of him and puts it on his readers. Never in my wildest dreams, did I think that not only would Pat read it, but that he would consider it to be published by Story River Books. It’s totally mind blowing.

So I was at his birthday party the October before he died, and again going back through the line and he’s signing another book and this time I said, “I want to thank you for publishing my book. I’m one of your Story River writers.” And he says, “Oh what’s your name?” And I told him and he says, “I don’t remember your name but what was the title of your book?” So I told him, and Mindy, he flung his arms wide open and said, “THE COW!”

And of course I’m crying and shaking all over. He took my hand and kissed it. Yeah so, it may have taken 27 years, but I’ll repeat what I said, to be escorted and ushered in to my publishing career via Pat Conroy’s enormous heart, it doesn’t get any better than that.

ML: And so speaking of ‘The Cow’ you use different points of view in the book to tell the story. Where did the inspiration for the cow’s perspective come from? Was it that morning on your family farm when you were awakened by the sound of cows calling?

BM: Oh yes. The cow that was in the deepest corner of that fence, it was old at the time and my father was about to sell her because that’s what happens to mama cows when they stop being reliably pregnant.

Daddy was about to sell her and I said, “No, no, no.” Because that’s the one that I made that deep connection with that day, with her eyes cut towards me, and made her a promise that day. So Mindy, I bought her from my daddy for a $1,000. And gave her sanctuary and that’s why she’s still alive today.

ML: And that’s Mama Red.

BM: Yes, the markings on the character’s face are her real markings. And the real Mama Red that inspired her is on the book cover.

ML: I have to tell you, I consider myself a fairly stoic individual when it comes to nature, but I had a little trouble reading some of your descriptions without getting a little emotional, particularly when Mama Red gets separated from her calf and tries to get back to him. What’s your take on that, how farmers deal with the realities that come with farming? Do you think we sometimes mistake being stoic for having no feelings at all?

BM: So I have a couple of answers. The first one I’ll say is they’re considered a business. I know that’s how my family does it. That it’s a business. That kind of keeps an attachment at bay. There are no names given or anything like that. And many of them have numbers in their ears. They’re just simply numbers. So I think if you’re going to do this, then it has to become a business and you kind of desensitize yourself.

However, and this is what I find interesting, my father was the very first 4-H Grand Champion winner in Anderson in 1941. My father was a very stoic—that’s a great word—very conservative, crusty Southern Baptist farmer and he could not talk about that experience.

He was 14. He got $330 in 1941, the equivalent of about $5,000 today. His picture was put on the front page of the newspaper above the fold. He was a big shot. He got free lunches all over town. It was a huge, huge thing. So I was trying to find out about it, get some details about the experience. My father’s eyes would mist over. He could not talk about it.

The other story I will tell you is, in my research I went to Kentucky where they still do this practice of the show and the sale. So I was in Ashland, Kentucky in 2010 and was introduced to the youngest little boy who was showing cows. His name was Ryan and I went over and I talked to him and told him I was writing a book. And I said what are you doing here Ryan? He said, “I’m going to show my steer.” And I said, “Then what are you going to do, sweetie?” His bottom lip began to quiver. His eyes misted over. He took his eyes from me and reached out and touched his steer, and then he brought his eyes back and says, “I’m going to kill it.” And I said, “Oh honey, I’m sorry.” And he said, “But not tonight.”

When the sale came around the next day he went missing. They finally found him. Now fast-forward six years. I went back last summer. He is now 12 years old. He had purple, Mohawk hair. And he was now laughing about the experience. So I think what you have to do is kind of numb up and desensitize to it.

ML: Would you say the selfless and even reckless devotion Mama Red has to her offspring in some ways serves as the vehicle by which Sarah Creamer comes to learn about caring for her own child, or what it means to be a mother and have that bond?

BM: Totally. The more drafts I wrote the stronger the presence Mama Red had. When I first started out, she was kind of minor, but in every draft she got more and more stage time. To the point where I did the last draft and…those sections just kept growing and growing as I saw that at its core this was a story about the relationship between a human mother and a bovine mother and what she had to teach Sarah. And so she got more and more stage time.

ML: And so there’s also those themes of the sacrifices we make for those we love or what we do or try to do to become better people for those we love. Was that also part of the discovery as you wrote this?

BM: Yes, it was the whole sacrifice business. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the difference between Sarah and Luther, the antagonist. They’re both striving to be good people and good parents. At their core they both want the same things. Sarah wants to be a good mother and have her little boy love her, and Luther wants his little boy to love him too and he wants to be a good daddy. So they both share a common goal.

What’s the difference between the two? And I started thinking about the sacrifice, the word you used a while ago. And I see Sarah and Mama Red both in service to who they love. They’re both in service to. As a contrast, Luther, who also loves his boy, needs his boy to be in service to him. So it’s this idea of being in service to someone. That’s something that I’ve learned and have been thinking about.

ML: I think it’s fair to say that much of the book was deeply personal for you. And so for writers writing something that is so close to their upbringing, or something they’re passionate about it, I think it can go one of two ways. If you’re that emotionally invested, you may not be open to editing or take the characters in a different direction than what actually occurred in life. Or, the story can have a tremendous sense of authenticity from the writer’s obvious devotion to it, and when you have read it you come away with the sense that there is nothing like it and no other way of telling it.

I believe that your book has fallen into that second category. But were you ever afraid of the potential to go down that first path or how did you work through that?

BM: You know, cows aren’t adored animals. I’m not writing about a dog, a horse, or a cat. So the only kind of push back I ever had in my mind was, “Oh my gosh, are people going to want to read about a cow? Is that going to be an issue?” But I didn’t let that live very long in me because it was my story and it was something I had to tell.

When readers say they found it authentic, or genuine, or they were there, or they could see it, or they could feel it, to me that’s a high, high honor. That’s what I want to have happen.

There are two kinds of stories. There are stories that entertain. They take us away. Your beach read stories. And then there are stories that help us endure as human beings. I want to be in that second camp. I want to help us endure as people. And to do that, I think you’ve got to get personal and be as authentic as possible.

You know Toni Morrison said if you write about something specific enough, you will touch the universal in us all. So when you think about Pat Conroy and how specific he was to his world, I mean I use him as, oh my gosh, as my example and what an example. I want to make my own world that specific.

ML: What’s next for you? Will you be visiting this place again of Mama Red and Sarah Creamer?

BM: I’m already writing another book based on that research I was telling you about when I was in no man’s land and didn’t know what I wanted to do with that other novel. But this has surprised me, the people who have said, “Will there be a sequel?” I’ve had several people to ask me that question. And I went, “Whoa.” I don’t know that to be the case, but I don’t know that to not be the case because I have sat and thought about what kind of man will Emerson Bridge be when he grows up or about Luther or Sarah. I don’t know, but I do know I am working on this next book I’m calling “Took” that’s also set in South Carolina that’s based on the Savannah River Plant.

ML: The bomb plant.

BM: Yes, the bomb plant. I did oral interviews with 30 or 40 people that had been thrown off their land. More than half of them have died by now. I am writing the story around, or making it as its centerpiece, the most dramatic story I heard and letting that centerpiece carry the story for all of them.

ML: That sounds exciting. I can’t wait to read it.

BM: Thank you.

ML: Well, that’s all I have. Is there anything you’d like to add or that I failed to ask or you think, “I can’t believe she didn’t ask this?” I’m sure we could talk all night.

BM: (laughing) I know! We have a lot in common. Are you going to be there Tuesday night?

McClain will be in conversation with novelist, Beaufort County native, and Pat Conroy’s Beaufort High School student Valerie Sayers, from 5:30 to 6:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 14, at the St. Helena Branch Library.

ML: Yes!

BM: I just want to tell you thank you again.

ML: Thank you and we’ll see you Tuesday on St. Helena.

About Mindy Lucas:

As a reporter for the State, Island Packet, and Beaufort Gazette newspapers, Mindy Lucas covered book news and literary events such as the South Carolina Book Festival and Columbia’s One Book, One Community city-wide “big read.” She also interviewed writers including Larry McMurtry, Ron Rash, Mary Alice Monroe, Ellen Malphrus, James E. McTeer II, and of course, Pat Conroy. Prior to her newspaper career, Mindy was a freelance journalist for publications around the southeast and an advertising copywriter. She is now a content strategist for a Columbia-based marketing communications firm and lives with her husband David and their cat Earl in Beaufort, South Carolina, just a bicycle ride away from the Pat Conroy Literary Center.

As a reporter for the State, Island Packet, and Beaufort Gazette newspapers, Mindy Lucas covered book news and literary events such as the South Carolina Book Festival and Columbia’s One Book, One Community city-wide “big read.” She also interviewed writers including Larry McMurtry, Ron Rash, Mary Alice Monroe, Ellen Malphrus, James E. McTeer II, and of course, Pat Conroy. Prior to her newspaper career, Mindy was a freelance journalist for publications around the southeast and an advertising copywriter. She is now a content strategist for a Columbia-based marketing communications firm and lives with her husband David and their cat Earl in Beaufort, South Carolina, just a bicycle ride away from the Pat Conroy Literary Center.

Mindy, thank you for this interview. LOVED your questions! I am so honored.

Thank YOU Bren. Enjoyed our conversation and looking forward to tonight!

I was deeply moved by this interview and ordering the book after I leave this comment. I live in Seabrook now but grew up in Ware Shoals and graduated from Furman – in ’74! Hope the St. Helena conversation will be rescheduled (assuming it was cancelled). I also hear the cries of the Mama Cows and am an advocate for a vegetarian diet. I hope to meet Bryn and/or Mindy one day soon.

Aww, thanks so much Karen. I just saw this reply! I’ve since started writing for The Island News and Lowcountry Weekly, which used to run these interviews when I volunteered for the literary center. At any rate, I’ve been busy with my new job, but I did so enjoy interviewing Bren. Come to Beaufort sometime and visit the center — the folks there are great and can tell you about Pat and the area’s rich history and literary connections. Best, Mindy Lucas