“A lot of people, I think, set out to write a novel that will accomplish something. And I guess I’m much more interested in writing a novel that will explore something–that will in some way enlarge my thinking….”

Beaufort native, Valerie Sayers, is the author of six novels including Who Do You Love and Brain Fever, which were named New York Times “Notable Books of the Year.” The film Due East was based on her novels Due East and How I Got Him Back. She rather publicly (and hilariously) challenged her fellow South Carolinian Stephen Colbert to give her most recent novel, The Powers, the famous “Colbert Bump.” Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Commonweal, Zoetrope, Ploughshares, Image, Witness, and Prairie Schooner, and has been cited in Best American Short Stories and Best American Essays. Sayers recently won her second Pushcart Prize for fiction and will be inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors, the Palmetto State’s literary hall of fame, in April of 2018. Sayers was a Beaufort High School student of Pat Conroy’s and serves on the board of directors of the Pat Conroy Literary Center. She lives in Indiana where she teaches English and fiction writing at the University of Notre Dame.

Mindy Lucas: Welcome to Porch Talk. For starters, let’s talk a little bit about your background in terms of where you were born and raised because as you can probably guess, I’m going to ask you about growing up here in a bit. Were you born and raised here in Beaufort?

Valerie Sayers: Yep, born and raised. I was born in 1952. I was the fourth of seven kids. So I’m right in the middle. I went to Battery Creek Elementary, Beaufort Junior High, and Beaufort High School.

ML: And when did you move away?

VS: I left when I was 17 after my senior of high school. I was hell bent for New York City. I thought I was going to be an actor. I had been acting in the Beaufort Little Theater because that was my fantasy. My father had gone to Fordham University in New York [Where Valerie also went.—ML] and as it happened they were starting a brand new experimental college at Lincoln Center with an emphasis in the arts.

ML: What were your parents like or what did they do?

VS: Well, my parents were Yankees.

ML: (laughing) Is that an occupation?

VS: (laughing) So many people in Beaufort are. My dad was a psychologist – a civilian psychologist at Parris Island and my mom was raising seven kids. So they were very supportive of my going to New York.

ML: Really?

VS: Yeah, they thought it was a good idea. They always loved New York City and spent part of their own youth in New York, so they knew the city well and they were all for it. So I did. I took off and it took about six weeks probably for me to decide that I really didn’t want to be an actor, that it was a very hard and miserable and competitive life. So I spent a good portion of my college days figuring out the next step. But you know I had written all my life. I threw myself at literature courses in college even though I never declared an English major at the time.

ML: Is that right?

VS: Yeah, it’s interesting. I teach in the MFA program now and we find about half our students were not English majors. It’s fascinating.

ML: That is. When I started in the newsroom, we had quite a few people who didn’t necessarily start out as journalism majors.

Let’s talk about the town of Due East in your work, not to be confused with Due West, South Carolina. I believe I read where this is a thinly veiled Beaufort?

VS: Yeah, it’s totally Beaufort. You know I’m not sure exactly why I didn’t call it Beaufort. I actually stole the name Due East from a dear friend, a writer friend and classmate. And I just took it.

ML: You’ve written about the town in your books Who Do You Love and Due East and in those books you also explore themes of relationships, loneliness, your characters’ inner desires or their plight. It seems like that’s what you build your framework around. First, can you describe the bigger themes of your work instead of me saying what I think they are, and then would you say if these are what you continue to come back to?

VS: Yes, I think you’ve done a good job of listing the central, or I guess I would call that list the central basic human concerns. I often have thought of my work, particularly certain novels and certain stories, as veering much more in the direction of very particular moments in history. So my novel Who Do You Love takes place in the 24 hours before John F. Kennedy is assassinated and is very much about the changing political terrain of the small town South.

Or, in my novel Brain Fever, the main character, who is having a crack up, is actually consumed with the situation of the civil war in Bosnia and what’s happening to the Bosnian people even though half the novel takes place in this little Southern town. But that was inspired by people I knew in Beaufort who were anti-war activists during the Vietnam War for example. And that was a very lonely thing to be in Beaufort because, of course, it was such a military town.

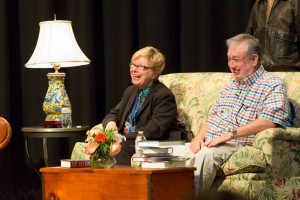

Valerie Sayers with Bernie Schein on stage at the Pat Conroy at 70 festival, October 2015, Beaufort, SC

ML: You’ve been compared to Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor for your characters and voice, possibly since the characters that people your world are a little askew or off course? But tell me how you describe them and what do you think of that comparison?

VS: You said it very well. I actually teach, as often as I can, a course in Southern Literature. I teach McCullers and O’Connor, both of whom I hold in very high esteem.

When I was a young writer, it was Faulkner really that I fell love in love with. And the idea of using the place of Due East was absolutely a Faulknerian move. That was my own little homage to William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha.

But certainly McCullers, O’Connor, and Walker Percy is each a great example of a Southern writer who had a really profound impact on my thinking about what it is a novel can do and should do. Those are all really important people to me and they, like all novelists I guess, are always interested in that central question of the individual in a culture and how often the individual feels estranged from a culture or estranged from even bigger questions—questions about existence and the, capital M, Meaning of, capital L, Life.

ML: When did you realize this was going to be the backbone of everything you write? Was there a moment in your writing career or were you right off the acting thing when you realized I have a lot to say?

VS: (laughing) A lot of people, I think, do write because they have a lot to say. I had a wonderful professor in my undergrad education. I signed up for what I thought was a fiction-writing workshop. It was good mistake. It turned out it was a poetry-writing workshop.

I had written poetry all through my childhood and I thought I had put it away. So I had no interest in taking a poetry-writing workshop, but I just loved this guy. He came in on the first day of class and he said, “I hope you don’t think you have to something to say.” He said, “I follow W. H. Auden who said, ‘Writers shouldn’t have something to say. They should be interested in how they’re saying things.’”

And that was such a challenge to everything that I had always believed about writing—how writers had to have a strong, philosophical perspective at the least. But I just loved it as a notion.

ML: It seems like that would be good training for what you need to do to collect the things you need to collect for writing a novel?

VS: Yeah, I think that’s absolutely right. A lot of people, I think, set out to write a novel that will accomplish something. And I guess I’m much more interested in writing a novel that will explore something–that will in some way enlarge my thinking, which, believe me, is puny.

ML: (Laughing) Let’s shift now to your short story “Tidal Wave” that recently won the Pushcart Prize. First, can I just say how elegantly written and structured this story is. It’s so unvarnished without any overly wrought sentimentality or adornment.

VS: Thank you so much. That’s probably the 457th draft of that story.

ML: Well, and that was kind of what I was going to ask you. Did you begin with the idea of this woman, Vonda, that the narrator is remembering, and what a great name, by the way. And I say that with no sarcasm or irony. It’s a great name.

VS: Thank you.

ML: But did you begin with the idea of the narrator? Or did you begin with the time and the place or did both of those things evolve at the same time?

VS: The story is actually inspired by a very dear friend who doesn’t live in Beaufort anymore but has had a house there for many years and visits when she can. But she was not a real close friend in high school but she was part of a circle of girls. And she was exquisitely beautiful then and now in very different ways. And she became a cheerleader.

And so I had a Christmas coffee with her one year, and I hadn’t seen her in years, and I was very struck by how beautiful she still was and how different her beauty was with age and by who she had become. As I said, I was not real intimate with her in high school. But she had become a feminist, and I just found that fascinating.

So originally, that’s all I had. I had a vision of her face and an idea of another, older woman trying to write about this ethereal beautiful creature from her youth. And it was about high school and all the conforming pressures of high school. I knew from the very beginning that I wanted to start it, at least, in this collective voice – that it would be a plural voice telling the story rather than a singular voice, but it would also be really clear that it was one woman that was narrating the story.

So that’s how I started and you know I just began with that first scene of cheerleader tryouts. And the rest she just becomes kind of this mythical creature.

Originally, I had thought this was a story I was going to dedicate to my friend Rita, but as soon as I wrote the second paragraph I thought, ‘Well, I don’t want her thinking she is this person,’ because it doesn’t in anyway tell the story of her life at all. You know that’s what fiction is for – to make up somebody else’s life. So it’s not her story at all except those core things: beautiful, cheerleader and sort of magnificent and fierce. So yeah I was just flying blind with that one.

ML: And so how many drafts did you really go through? Quite a few?

VS: An uncountable number of drafts. I always tell my students this, but I didn’t write short stories for just the longest period of my life. That’s what I wrote when I was in graduate school, and I was so bad at it. I really never wrote a successful short story when I was in graduate school. I just thought, ‘I don’t have a gift for that.’ Stories are just very, very difficult for me.

ML: I agree. I’ve tried my hand at it and yes, they do seem difficult.

VS: Yeah, and yet that’s where we always start our students.

ML: And so we see the storyteller and her friends in the present trying to find glimpses of their elusive friend on Facebook. And they finally find some mention of her and so two things occurred to me here.

First, I found myself chuckling over these women trying to stalk their friend online. But it occurred to me, we never really know a person and what they’ve endured or are enduring and especially as time goes by. We think we know a person and maybe we do but perhaps not. And now social media seems to be complicating that somewhat.

VS: I’m actually not on Facebook myself for complicated reasons. And maybe one of the impulses to separate myself from that area was born of that appreciation I had for rediscovering this friend later in life and having these wonderful face-to-face encounters with her.

I ended up visiting her several times as frequently as I could, because I just felt such a strong attraction to her and bond with her. She was very close to Pat. Pat adored Rita and we ended up going to the funeral together. And it was so wonderful to have her there and have that span of shared history.

ML: The second thing that occurred to me as I read “Tidal Wave” was that there is just such a quiet desperation there. It’s the kind of story you want to re-read when you’re finished to see if you feel the same way about the narrator at the end or if your first reaction is the right one, if there is such a thing. I mean, is she devastated, and that might not be the right word, or impacted by how her friend’s life affected her or is she okay with it for the most part?

VS: I think that’s a very accurate reading. I’m glad it had that effect.

I’m so influenced by Flannery O’Conner’s short stories and you know she had these moments at the end that are just so fabulously heavy-handed but also peculiar and unsettling and mysterious. And so I often worry that I’m just pulling an O’Conner – that it’s too transparently an imitation of her. And that was something I struggled with a lot at the end with trying to get the right balance and to remain true to a woman who is kind of telling us from the very beginning that in a way she has always been afraid of stepping out of line.

ML: And of course Due East, their hometown, has such a presence as well in the story. You manage to pack quite a bit into six or seven pages so that you come away with the scale or grandeur of a novel all in one tidy story. I honestly marvel at how you’re able to do that.

And that maybe where the drafts come in. How do you handle that? Did you tell yourself I’m writing a short story, but I’m not necessarily going to go on with this whole world so that it becomes a novel?

VS: This is one that I definitely knew from the start that I wanted it to be a short story. I even knew how long I wanted it to be. I set myself some constraints. Sometimes I don’t abide by them. I find it useful and challenging in sort of equal measure to set some kind of constraints before I start.

So the constraints for this one was it was going to be roughly X pages and it was going to have this collective “we” voice and I hadn’t played with that very much so I thought that might be fun.

So, then the first draft I didn’t know what I was doing. I didn’t know where I was going. I didn’t know really why I was writing this story. That is the way I prefer to write, which is not very useful when you’re writing a novel. (laughing) With novels, you really do have to take yourself in hand and figure out what it is you’re doing earlier than the completion of a first draft.

But with stories, I’m pretty comfortable working that way and then at the end, when I see what I’ve got and what was uncovered in the process, then I can go back and start slapping that baby into shape.

Classmates of the Beaufort High School Class of 1969 with their teacher: (left to right): Harry Keyserling, Valerie Sayers, Pat Conroy, Rita Thetford Bostick, and Guy Matthews.

ML: With that in mind, let’s circle back to your connection to this place—to Beaufort—and when you went to Beaufort High School, and, if you’d like, please tell your Conroy story.

VS: Pat was just a god. It’s just so funny to think how young he was then. Because we were, you know, 17 years old, 18 years old, 16 years old. He must have been 22 or 23 when he taught us.

We just thought he was so sophisticated and witty and erudite. I thought he knew everything. Maybe he did. (laughing) He was very good at projecting that sense.

So my Conroy story is the one I actually wrote for Jonathan [Haupt] for a collection of essays that he and Nicole Seitz are putting together. It was really interesting to remember, to think about particular moments in that experience of being his student.

The one that always strikes me most deeply and really moved me is when his parents came to visit our psychology class. I thought they were beautiful. They looked like the perfect parents for Pat Conroy. They kind of swept into the classroom, and they stayed for about 15 minutes and then swept back out. And Pat just gave this very together lecture. He was a big lecturer, which is quite a skill I’ve come to find out. But he could really talk at length, extemporaneously.

He was very handsome and he projected all this self-confidence. So what was really moving about this moment was when, after they left and he saw them out, he came back and he was just white. And we could see that he was sweating and he sort of just broke the wall of authority that he held over us by saying, “That was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

He seemed genuinely shaken by it. It was one of those moments where you felt like somebody was giving you this great gift of exposing himself and allowing you to realize how much he had held himself together to present himself as this ideal son to his parents. It was a very humanizing moment, and I already adored him but I really, really liked him after that.

ML: What a great story. And I understand the character of Mr. Thigsby in “Tidal Wave,” was a sort of hodgepodge of Conroy and other teachers?

VS: Yes! Mr. Thigsby for me, I had all of the above in mind: Pat, Pat’s great mentor Gene Norris, Millen Ellis who is the other teacher he mentions from time to time in his work, and a wonderful South Carolina poet and writer, Starkey Flythe, who just died a couple of years ago. He taught at Beaufort High a couple of years before I went there.

All those male teachers at Beaufort High School were unbelievably smart, interesting, crazy interesting and challenging. They gave us unbelievable things to do. One time for our final exam, Mr. Ellis had us to write in a Faulknerian voice! But it was really challenging stuff for yahoos the way we were. And Pat just clearly loved being in that environment. He relished being in front of a classroom, and I think he adored his students as much as they adored him.

Valerie Sayers interviews Bren McClain during a March 2017 Visiting Writers Series event of the Pat Conroy Literary Center

ML: You will be inducted into the South Carolina Academy of Authors next year in a ceremony here in Beaufort. What has the thought of that been like for you?

VS: Well it’s such a lovely honor. It’s a real tickle that it will be in Beaufort. My mother is 99 years old. And she will be 100 when that event happens. So I’m just holding my breath. She’s still getting around, so I hope she’ll be there because really that honor would be the ultimate for her.

ML: I think that’s a great place to end. Is there anything we talked about that you think is important to add or that you’re thinking I can’t believe she didn’t ask?

VS: No! It’s been a delightful conversation. Those were great questions, so I don’t think I have a thing to add.

About Mindy Lucas

As a reporter for the State, Island Packet, and Beaufort Gazette newspapers, Mindy Lucas covered book news and literary events such as the South Carolina Book Festival and Columbia’s One Book, One Community city-wide “big read.” She also interviewed writers including Larry McMurtry, Ron Rash, Mary Alice Monroe, Ellen Malphrus, James E. McTeer II, and of course, Pat Conroy. Prior to her newspaper career, Mindy was a freelance journalist for publications around the southeast and an advertising copywriter. She is now a content strategist for a Columbia-based marketing communications firm and lives with her husband David and their cat Earl in Beaufort, South Carolina, just a bicycle ride away from the Pat Conroy Literary Center.

Leave A Comment